Problem: Writing XPaths is hard and confusing when there are no unique identifiers

XPath (XML Path Language) is a query language for selecting nodes from Document Object Models (DOM) like XML, HTML, etc. XPaths are frequently used with Selenium scripts to uniquely identify elements in page. This post is a descriptive tutorial on how to think about xpaths and write xpaths in the absence of unique identifiers.

Why this post?

In most web apps, testers do not find unique identifiers (like ids) to locate DOM elements easily. For a long time now, I have used both CSS selectors and XPaths to uniquely identify DOM elements as part of our Selenium automation scripts. The standard XPath tutorials on the web cover the syntax and the terminology but do not cover the thought process behind arriving at an XPath in the absence of ids or other unique identifiers. Over the years, I found that despite my colleagues having access to Google, I have had to spend a significant amount of my time teaching them art of writing good XPaths. While helping my fellow testers, I realized that the number one difficulty was to get the testers thinking correctly about XPaths. In this tutorial, I have decided to document the thought process behind arriving at an XPath when you do not have unique identifiers to work with.

Basics of XPath syntax

For newbies, I’ll give a quick run down of the basics of XPaths.

1. XPaths usually begin with a double slash i.e., //

2. reference html elements by its tag. So a link can be referenced by /a

3. to reference attributes of a HTML element use the @ notation

4. text() and dot are special attributes of HTML elements: text() refers to the text within the element while dot is a substitute for ‘any attribute’

5. keywords contains and equals are useful for uniquely identifying nodes

The 3 most common XPath patterns

Most tutorials on XPaths will expose you to what I consider the three most common XPath patterns in a tester’s tool belt:

1. //html_element[@id=”blah”]

2. //html_element[@attribute=”value”]

3. //html_element[contains(@attribute,”value”)]

You can usually get some amount of Selenium automation working with just the above three patterns. But it is going to be a pain to maintain. I think XPaths get a bad rap simply because most testers do not evolve to using better XPaths. Here’s hoping we can change that!

The better way to write XPaths

In real life, things are rarely this straight forward. Not all nodes have ids or unique attributes. You need to come up with relative paths to known nodes and then proceed to your destination node. XPath axes are a powerful tool and very useful in specifying relative position like parent, child, sibling, ancestor, descendant, etc.

I treat coming up with XPaths like following directions given to me by a human – imprecise and non-unique at each step, but when strung together are good enough to locate places accurately. So here goes a real life example of following directions before tackling the more advanced xpaths.

Scenario

Your friend Jose calls you up:

Jose: Hey, want to checkout the new bar that opened near my place?

You: Sure

Jose: Drop by my place whenever and we can leave from here

You: All I remember about your apartment was that it had a ton of flags as decoration. Remind me – how do I get to your place?

Jose: Do you know Bobby Street?

You: Yep

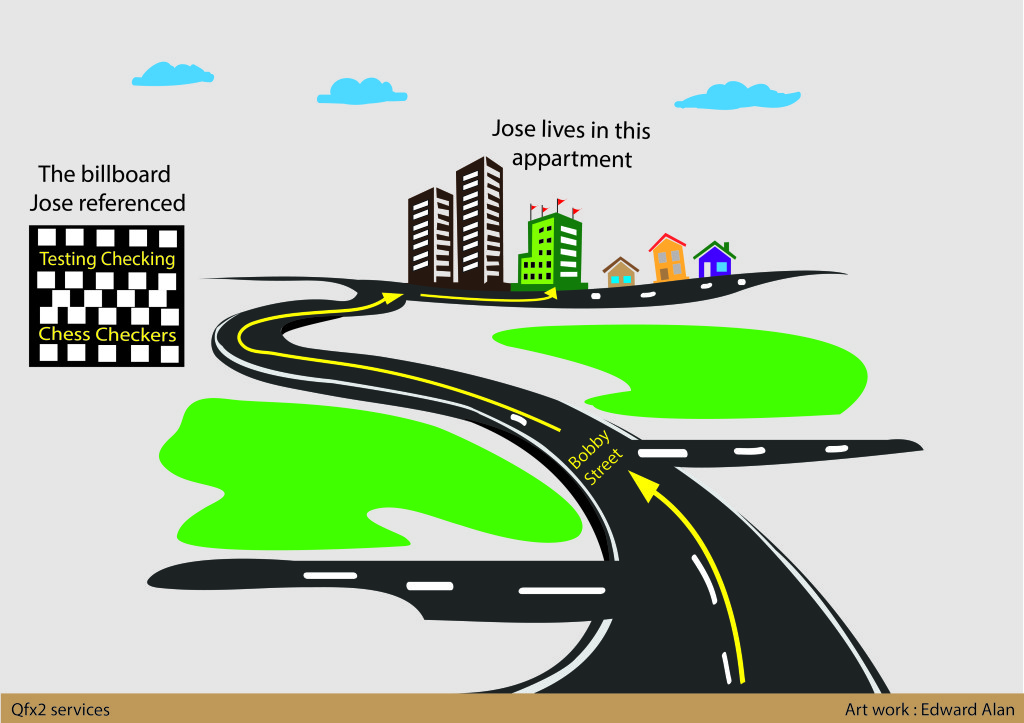

Jose: Keep driving down on Bobby street. You will see a billboard that reads ‘Testing: Checking :: Chess: Checkers‘. Take the first right after that billboard. Keep driving and you should see my apartment to your left.

You: What is your apartment number?

Jose: I live in A-block and my apartment number is 602.

Guess what? You can now follow the directions rather easily even though each step of the directions above is non-unique. In your city, there are likely many billboards with the text ‘Testing: Checking :: Chess: Checkers‘ but on Bobby street there is possibly only one. There are likely many apartments on the street Jose lives but likely only one with flags as decoration. Further there could be many A-block, apartment number 602 in your city but within Jose’s apartment it is likely to be unique. You can make sense of this imprecise set of instructions because there is a pattern to the way your brain is solving the problem.

Algorithm in real life

1. identify a known landmark closest to your destination (e.g.: Bobby street)

2. identify a series of easily recognizable, fairly unique features between the landmark and your destination to get to the vicinity of your location (e.g.: billboard text, flags, apartment)

3. use unique identifiers within this narrowed focus to zero in on the location (e.g.: A-block, apartment number 602 within the apartment with flags)

PRO TIP: choose landmarks and identifiers that are less likely to change in the time frame that you plan to use them

Applying the algorithm to write XPaths

If I converted the above directions to an XPath, it would look like this:

1. Start with a known landmark closest to your destination:

//street[@name='Bobby Street'] |

2. Identify the billboard

billboard[text()='Testing: Checking :: Chess: Checkers'] |

Sewing what we have till now, our XPath looks like this:

//street[@name='Bobby Street']/billboard[text()='Testing: Checking :: Chess: Checkers'] |

3. Take the next right

following::street[@direction='right'][1] |

The following keyword is a very useful xpath axes. Also, XPath indices begin at 1 and not zero.

Sewing what we have till now, our XPath looks like this:

//street[@name='Bobby Street']/billboard[text()='Testing: Checking :: Chess: Checkers']/following::street[@direction='right'][1]/ |

4. Identify the apartment (it has flags as decorations)

apartment[contains(@decoration,'flags')] |

The keyword contains is often useful when equals is not enough.

Sewing what we have till now, our XPath looks like this:

//street[@name='Bobby Street']/billboard[text()='Testing: Checking :: Chess: Checkers']/following::street[@direction='right'][1]/apartment[contains(@decoration,'flags')] |

5. Zero in on the location

descendant::house[@block='A' and @number='602'] |

BTW, did you notice the other apartment on the same street? If you have searched for just house[@block=’A’ and @number=’602′], it is likely that you would have found a match in that apartment too. This is the reason that we had to narrow our focus, in Step 4, to the apartment with flags as decoration.

The keyword descendant is very useful when you have multiple children, grand-children of the same type.

Putting it all together, the XPath you want is:

//street[@name='Bobby Street']/billboard[text()='Testing: Checking :: Chess: Checkers']/following::street[@direction='right'][1]/apartment[contains(@decoration,'flags')]/descendant::house[@block='A' and @number='602'] |

And there you have it – a tutorial on the thought process behind writing XPaths. I hope you found it useful!

P.S. 1: I have used a rather unusual approach to explaining XPaths – no HTML at all. Let me know your feedback

P.S. 2: I am not going to write about CSS selectors because there is already a fantastic resource: http://flukeout.github.io/

P.S. 3: I have referenced 2 former world chess champions in this post. Can you guess which two?

I want to find out what conditions produce remarkable software. A few years ago, I chose to work as the first professional tester at a startup. I successfully won credibility for testers and established a world-class team. I have lead the testing for early versions of multiple products. Today, I run Qxf2 Services. Qxf2 provides software testing services for startups. If you are interested in what Qxf2 offers or simply want to talk about testing, you can contact me at: [email protected]. I like testing, math, chess and dogs.

Nice article the way you explained is very good i want to add one more point we have some plugins also by which we can directly get the xpath of an element such as xpath viewer, selenium ide etc .

see this once here are some way to get xpath

Thanks!

@Eathen I find most plugins do not do a good job of coming up with robust xpaths. At Qxf2, we use XPath Checker, Firebug 2.0 and (old, works only with FF 3.6 and below) XPather to confirm our hand crafted xpaths are correct.

I agree with your point some how, I have worked with selenium IDE , I used to record my steps then used to see the elements address from the IDE and I always found 90% correct xpath’s working with Webdriver.

See more related question of xpath